The Purpose of Regulation, Then and Now

You can’t turn on the internets these days without encountering some new call to impose regulations on technology. The mantra “regulate technology” seems to describe journalistic sentiment about everything from AI and social media to ICOs and IoT.

This of course includes digital assets, one of the few emerging technologies actually targeted by regulators in 2018. And if you’re among those calling for the government to regulate technology, you might be tempted to hold up the SEC’s action on digital assets as a model for regulating technology.

In reality, the inverse is true—there is most certainly a better way to do it.

Now, you’d probably expect a co-founder of OpenRelay—a company whose mission is to make digital asset infrastructure available to all developers, whether or not they understand its complexities—to advocate for less-burdensome regulation. And you wouldn’t wrong.

But here’s the thing. At OpenRelay, we don’t believe all regulation is an undue burden—just regulation divorced from purpose.

“Wait a second! the purpose is to protect the public from predatory investment schemes! That’s been clear all along!”

If some version of that thought just went through your mind, you’re conflating ‘purpose’ with ‘goal’, and the distinction is crucial. As with most actions taken by governments, the goal of regulatory action is the realization of the end it seeks—in the case of digital assets, the goal is consumer protection. A worthy goal!

Purpose is another animal altogether. To understand it, let’s do a little thought experiment:

Imagine you’re an elected representative, and you’ve just been appointed to a committee responsible for recommending legislation to protect citizens from the dangers posed by predatory animals. Your colleague, Representative Ursa, proposes a bill whose goal is to end the suburban coyote epidemic currently ravaging the nation. Given the well-publicized harms the nationwide coyote infestation has caused in your district, you are 100% on board—but then you start reading Ursa’s proposal.

If adopted, the bill would create a new federal agency, the “Bear Establishment Commission (BEC)”, and grant it rulemaking authority for the purpose of “establishing sustainable grizzly bear populations in all major suburban centers nationwide.” Apparently, Ursa thinks this is the best way forward, since bears are natural predators of coyotes. Obviously, you’d join the rest of the committee in voting ‘no’ on this bill despite the fact that you agree with its stated goal. What you disagree with is the means—the purpose of the proposed regulatory regime.

While this is a silly example, this sort of disagreement over means—over the purpose of regulation—serves as an important sanity check, protecting us from the unintended consequences of regulatory intervention.

Maybe the prospective means don’t clearly map to the sought ends, or they impose conditions worse than the problem they’re meant to solve, or there are more appealing alternatives available. Whatever the case may be, regulatory power, once granted, is hard to take back. So when our elected representatives decide to regulate something new, carefully tailoring the purpose of the proposed regulatory regime to suit the goal is paramount.

“But doesn’t the SEC already have a proven system?”

The SEC has been around for a long time, faithfully executing its mission to protect investors from fraudulent securities offerings. The means it uses—extensive mandatory information disclosure, strict licensure requirements, zealous compliance policing, and strict enforcement of no-nonsense civil and criminal penalties—just doesn’t port well to digital assets.

But let’s put a pin in that for a minute. To understand why the status quo doesn’t make sense for digital assets, it helps to understand why the SEC’s purpose made sense in the past.

Our story begins in the late 1920’s, on a dark and stormy Thursday morning….

The Stock Market Crash of 1929 and its Impact

On Thursday, October 24, 1929, 11% of the value invested in the U.S. stock market evaporated in early trading, setting off a chain of events that would see the Dow Jones Industrial Average recede from a September 3, 1929 high of $381.17 to just $41.22 by July 8, 1932—an eye-watering loss of 89% and the lowest closing price recorded for the Dow in the 20th century.

This dramatic loss of wealth most likely contributed to another cause of what later became known as the Great Depression, bank runs. While only about 650 banks failed in 1929, the number would rise to more than 1,300 the following year. By 1933, nearly 11,000 banks, or about 40%, had failed.

But what really happened?

The Pecora Commission

While there is debate among economists as to the causation—whether the market collapse and mass bank failures were the cause of the Great Depression, or vice versa—Congress needed practical answers to guide emergency policymaking. So on March 4, 1932, under the guidance of the Senate Committee on Banking and Currency, an official inquiry into the causes of the 1929 crash began. In January of 1933, Ferdinand Pecora was appointed as chief counsel for the Committee on Banking and Currency, inheriting the task of writing the inquiry’s final report from his predecessor. After his appointment, he discovered that the investigation was incomplete, and requested an additional month to hold hearings. Newly-appointed committee chair and old-timey mustache afficianado Senator Duncan U. Fletcher assented with a little encouragement from President Franklin D. Roosevelt.

Making Yosemite Sam jealous since 1932.

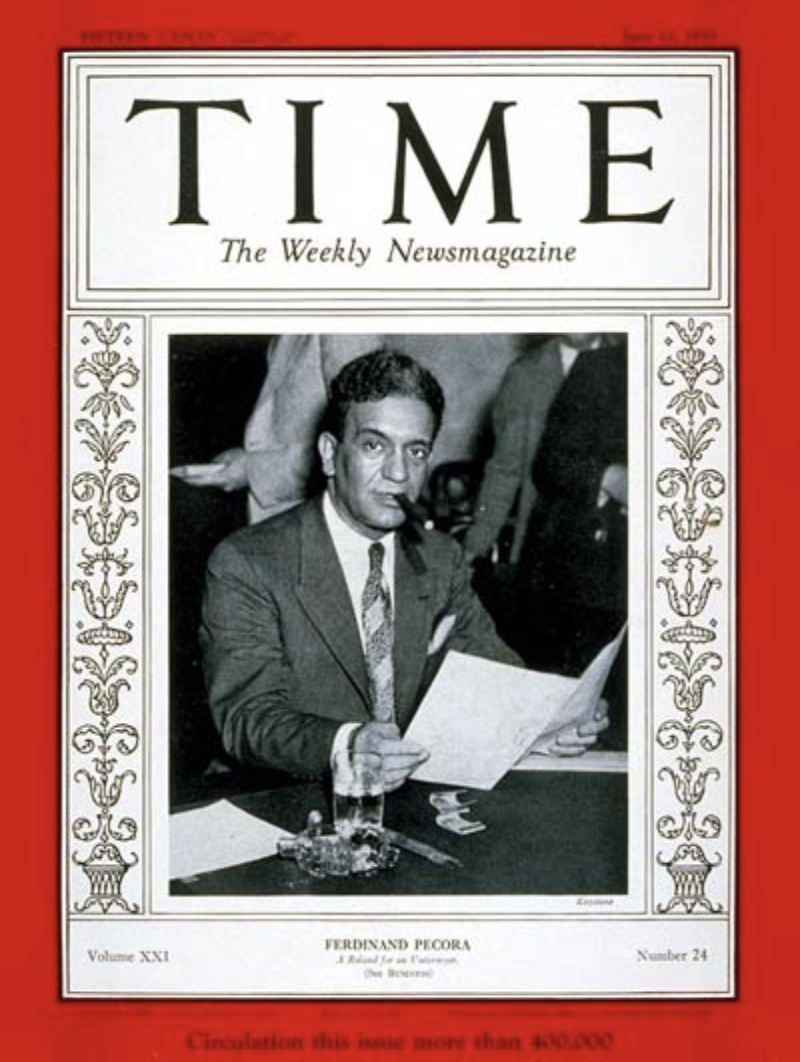

Unleashed, Pecora relentlessly pursued his mandate, and the investigation—previously criticized as ineffective—found itself with a set of sharp new teeth. Pecora’s zealous pursuit of answers was so effective at eliciting damaging testimony from the day’s titans of finance, including household names like J.P. Morgan Jr., that the commission became popularly identified with his name, and what started as an extra month turned into more than a year. His public notoriety was so far-reaching that in June of 1933, Time Magazine featured him on its cover.

Pictured: Ferdinand Pecora chuffing a huge cigar next to a giant ashtray and two matchbooks. T'was a smokier time.

The Pecora Report: What it Says (and What it Doesn’t)

The final hearing ended on May 4, 1934, and just over a month later, Pecora’s final report was published. Weighing in at 395 pages of gripping (well, surprisingly readable at least) prose, this report is a monster.

The story it tells is credited with galvanizing public opinion in support of a massive overhaul of the U.S. financial system, including the Securities Act of 1933 and the Securities Exchange Act of 1934.

In short—it contains nothing less than the purpose of the SEC.

What it Says: the quick-and-dirty version.

- Widespread adoption of communications technologies in the 1920s made it possible for the public to watch and react to the movements of the securities markets, as well as passively participate through investment funds managed by a small number of active participants.

- Because it takes time for information to travel, active participants—insiders like exchange operators, brokers, investment fund managers, bankers, and owners of companies raising funds by issuing securities—have immediate knowledge before it reaches the general public. (This is what is meant by the phrase ‘asymmetry of information’.)

- Margin trading not only intrinsically anchors the credit system in the performance of securities markets—it enables insiders to profit from information asymmetries created by the latency in communications, and it exposes the credit system to market-volatility-induced harms.

- With no oversight, insiders were free to engage in unrestrained self-dealing, using the public’s investments in managed funds to manipulate prices to insders’ advantage—often at the expense of the public’s investments.

- The cure for this lack of transparency and oversight provides justification for the mandates imposed by the 1933 and 1934 Acts—to be administered by a new federal agency—the SEC.

What it Doesn’t Say

In 395 pages, no mention of the technology used by exchanges to keep track of trades is mentioned. This is unsurprising, because in 1934, they had one option—pen and paper in a double-entry transaction ledger.

Since it goes without mention, and it was literally the only tool available (and had been for centuries), it would be unreasonable to conclude that the problem had anything to do with the technology used to keep the books.

While it does touch on the topic of exchanges very briefly (pages 77–80), it isn’t concerned at all with the technology exchanges use to keep track of transactions, and it certainly doesn’t contemplate the possibility that several companies could provide trade settlement, order publication, and a ‘user interface’ for traders.

And really, how could it? This would’ve been nonsense in 1934.

Putting it Together: The SEC’s Original Purpose

The SEC’s purpose is to prevent insiders from using the vast institutional pools of investment capital provided by passive investors for personal enrichment. The means by which the SEC acheived that end— mandatory disclosures, licensure, oversight, and strict enforcement via tough civil and criminal penalties—prevented insiders from double-dealing in secret by requiring disclosure of facts and conflicts of interest to which only insiders were once privy, and imposing significant consequences for non-compliance.

Through this mechanism, faith in third party money managers and financial institutions was restored, and the public ultimately began to trust insiders with their investments again.

Why the Same Approach Doesn’t Make Sense for Digital Assets

There are no ‘passive’ traders of digital assets on decentralized exchanges.

If you are trading digital assets on a decentralized exchange, you control them directly. They never leave your possession until your offer is accepted by a trading partner, at which point the assets move directly between your wallets. No third parties ever take custody.

Put simply, if everyone’s an insider, there aren’t any passive investors to protect.

Decentralized exchanges are decentralized.

Currently, the definition of an exchange doesn’t contemplate the possibility of an exchange composed of three or four different independent companies. Taken individually, each company does not meet the definition of exchange. It is only when taken together that something resembling an exchange materializes.

In cases like this, which company is ‘operating’ an exchange? Is it the front-end developer, the order book infrastructure provider, the settlement protocol or the KYC service? Is it all of the above? Or is it none?

Under the current regulatory regime, the answer is unclear, creating a need for legislative action.

But what purpose should inform their actions?

The SEC was never meant to be a technological gatekeeper.

Back when the 1933 and 1934 Acts were written, the SEC wasn’t concerned with what color ink the exchanges used to record transactions, or the weight of the paper they used in their order books. The licensure of national exchanges was never intended to be a tool to govern operational details like that. To do so would exceed its mandate.

Yet the SEC is using the national exchange licensure requirement to act as a technological gatekeeper—preventing decentralized, peer-to-peer exchanges from lawfully trading securities while actively prosecuting operators of unlicensed exchanges.

Transparency comes standard, no conscription necessary.

A lot of digital ink has been spilled about the alleged anonymity of public blockchains, but the fact of the matter is, everything that happens on a public chain, is, well… public. It is impossible to move tokens from one account to another without creating a public record. That’s just how it works.

While authorities haven’t indicated such mechanism is under development, let alone currently in place, it is entirely possible to trace digital assets through any transaction that has ever occurred on a public blockchain.

Granted, it would be a new approach to a challenge traditionally addressed by regulations that enlist centralized intermediaries to enforce policy and law. It would inevitably come with some growing pains.

But growing pains aside, independent transaction monitoring to do things like prevent money laundering or enforce international sanctions would preclude any need to conscript private enterprise—eliminating costs and delays imposed by regulatory red tape in the process.

And by internalizing enforcement operations and the attendant cost, officials tasked with enforcement would be easier to hold accountable to the taxpaying public—incentivizing regulatory efficiency and effectiveness while promoting a more democratic and transparent society.

Conclusion

Over time, many things have been disrupted by technological innovation. As the Pecora Report illustrates, the SEC was established in response to the challenges of technology-driven societal change. And just as we once adapted our institutions with purposeful legislation and regulation via the Securites Act of 1933 and the Securities Exchange Act of 1934, it is incumbent upon us to purposefully adapt them again.

As with any new technology, there will be tradeoffs, and new challenges call for new purpose—to ensure the our regulatory regimes seek our loftiest goals, and uphold our highest ideals. The status quo will no longer suffice.

If this post resonated with you, and you want to help, please contact your elected representatives and tell them you support amending the 1933 Securities Act and the 1934 Securities Exchange Act, along with any other relevant statutes, to ensure the United States continues to lead the world by fostering tomorrow’s innovations and innovators.

You can get your elected representatives’ contact info at this website.